Contemporary humor research suggests that repeated refrains gain “humor-charged” properties: audiences learn to anticipate a comedy catchphrase line, and it becomes an emotional cue. Sometimes, it works. And other times…

Join us for this occasional series where we dare to ask the question: “You know that wacky catchphrase? Is it really funny? Was it ever funny? Does it still hold up today?”

We promise to be objective. Let’s have a look.

Standup comedy has historically leaned into a few stock characters:

The Storyteller.

The Wisecrack Artist.

The Social Commentator,

And even the Hard-To Categorize Wildcard.

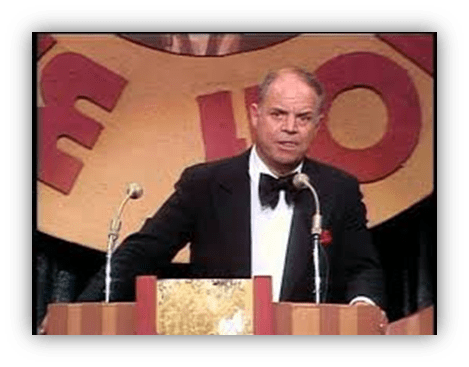

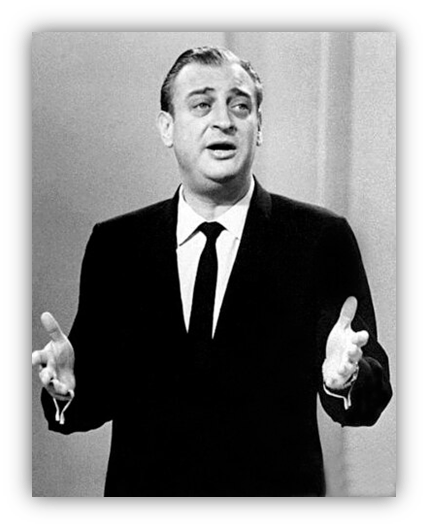

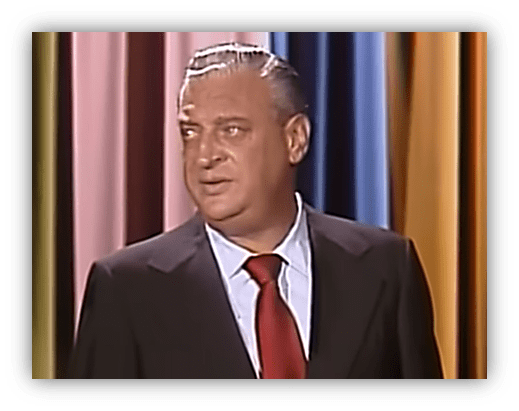

But one performer carved out an odder niche: he specialized in being the designated loser. His rallying cry? A line so familiar it practically walks into the room ahead of him: “I don’t get no respect.”

Rodney Dangerfield, born Jacob Cohen in 1921, had a rocky path to success as a comedian.

Early attempts in clubs during the late 1940s and 1950s went largely unnoticed. He left show business for eleven years, taking a job selling aluminum siding to support his young family.

This was where his quick wit, improvisational storytelling, and pitch skills were honed.

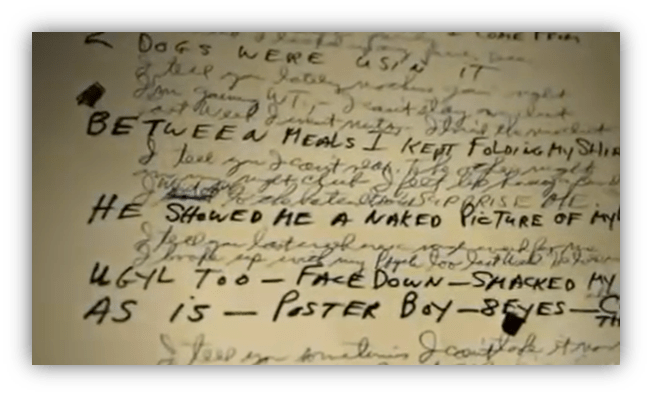

All the while selling home improvement, Dangerfield wrote jokes. And more jokes. A lot of jokes. A briefcase full of jokes.

Eleven years worth of jokes.

Jokes that experimented with various styles and voices. He kept writing, searching to find just the right hook to develop a persona that would make people laugh, and remember the guy who was up on the stage.

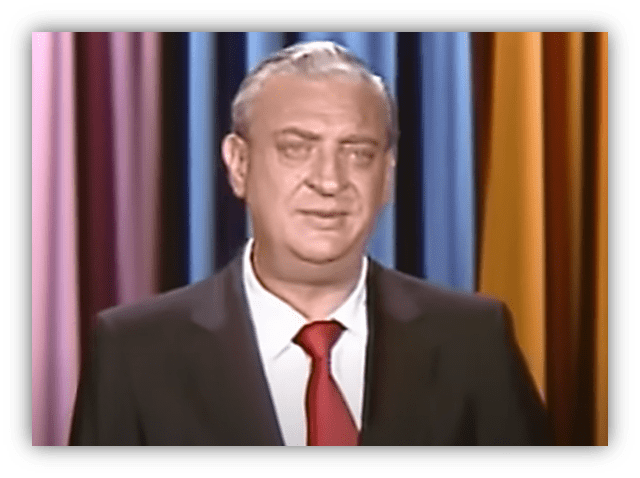

The genesis of “I don’t get no respect” was pragmatic and iterative.

“I had this joke:”

‘I played hide and seek; they wouldn’t even look for me,’” Dangerfield recalled in interviews.

Over time, he distilled the concept into a broader, more encompassing theme. It was a progression from:

- “I tell ya, it’s not easy being me,” to,

- “With me, nothing ever goes right,” to,

- “I can never get a break,” and finally to the simple, yet fully formed:

“I get no respect.”

He tested the bit relentlessly in the clubs at the Catskills resorts, the legendary proving grounds for many post-war comedians. Those audiences, often composed of working-class vacationers, responded instantly.

The line functioned as a communal gripe, allowing multiple punchlines to attach seamlessly.

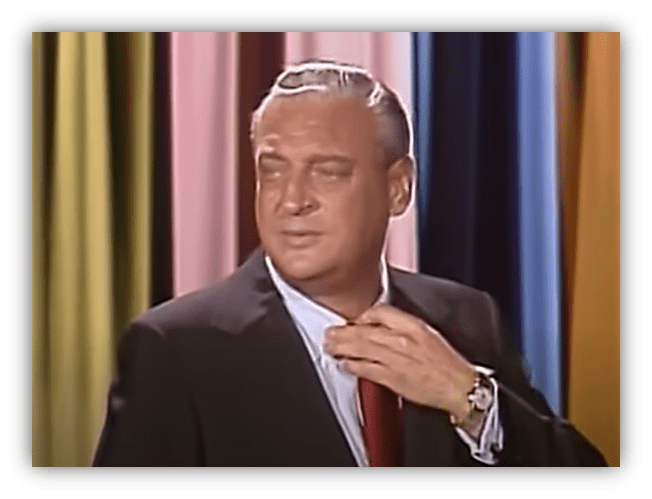

During the 1960s, Dangerfield refined the timing, cadence, and tie-tug gesture that became his signature delivery.

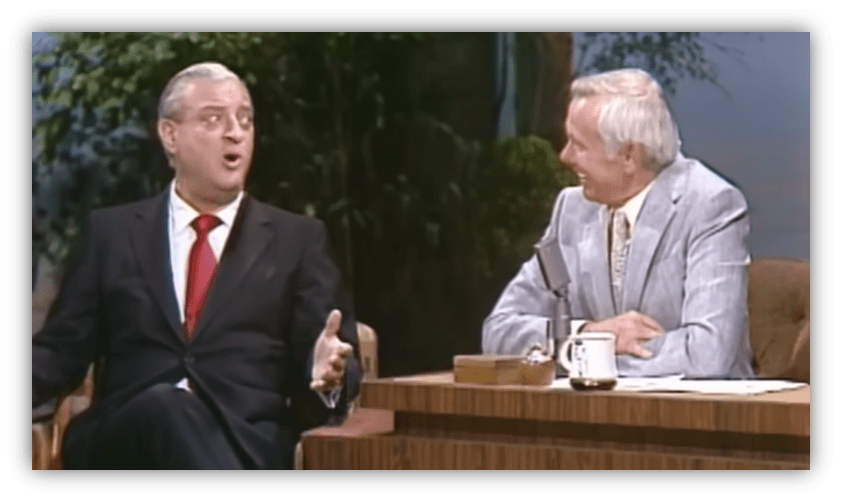

Latur during the 1970s and 1980s, Dangerfield’s “no respect” shtick fueled his rising star, with bookings in nightclubs, and eventually on television:

Including The Ed Sullivan Show.

The biggest breakthrough came in 1969 when he was asked to appear on The Tonight Show. The catchphrase struck a chord with the late-night audience, cementing both the line and the persona.

What began as a desperate workshopping of small complaints became a cultural shorthand for a lovable yet perpetually underappreciated comic.

He was a defeated and bug-eyed Everyman who distilled his misfortunes in a five-beat lament: “I don’t get no respect.”

The line functioned as an index: drop it into a room, and the comic’s definition was instantly resolved.

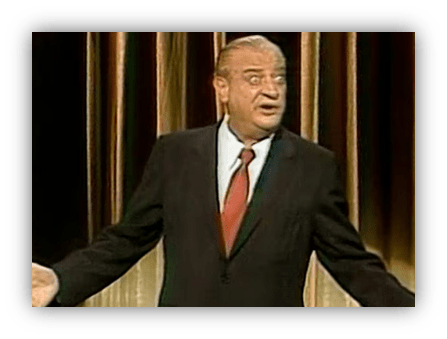

What looks on paper to be a simple gripe functioned instead as a comic engine; a refrain enabling Dangerfield to string dozens of sharp, discrete one-liners into a unified character sketch.

Why I Think It Worked

Three mechanisms explain the catchphrase’s potency, and why it landed:

First, persona through grammar:

- You’ve met this guy a hundred times: the self-defined born loser who publicly laments his lot in life.

The nonstandard double-negative (“I don’t get no respect”) encodes a working-class voice and comic immediacy.

Second, the semantic openness:

- The phrase is broad, so nearly any subsequent one-liner can be grafted to it. Like some sort of a desperate defense attorney aiming to save his client from the chair, Rodney keeps hammering away, building the case.

Instead of thinking, “Okay, I get it. Let’s move on,” you find yourself craving even more evidence of this guy’s pathetic shlubbery. In a good way, of course.

Third, the paralinguistic delivery:

- The shoulders, tie-tug, and the weary cadence punctuate the line like performance markers, turning a simple catchphrase into a credo.

All together, they create a linguistic shell that invites endless insertions without wearing thin.

But… Does It Hold Up?

It should have felt ephemeral. A single repeated lament is unlikely to sustain decades of popularity.

And yet, watching him deliver the line, it still lands, even decades later. The laugh is not at him, but with him. And partly at ourselves for recognizing the universalness he sketches:

“I don’t get no respect” evolved into a communal signal, an acknowledgment of small-scale human indignities.

Context matters. The catchphrase emerged in a post-war milieu—club culture, TV scarcity, audiences accustomed to repetition. Today’s media environment is faster, more context-sensitive, and less tolerant of the classic rinse-and-repeat standup chatter.

Yet, “I don’t get no respect” endures. Not because the world has stayed the same, but because the line a universal grievance. It’s a linguistic scaffold, and works as a shared social signal.

Leave a Reply